Key thoughts

“It was never seen as something schools would hold on to and determining how it was going to be used…schools should be offering it to their community, offering the training, the feedback to the community and let the community be self-determining about how they will use it.

When you really get whānau determining how it will be used then you’ll really be lighting the candle and spreading the flame of literacy at that level and when you can get it going in both settings, get it happening at schools and community, then you’re going to double the effect of literacy learning.”

Key questions

- What potential benefits do you see in working alongside your whānau and community with a literacy intervention?

- Who else needs to be involved?

- How might you create a context where whānau

can be self-determining about how literacy or any

other koha will be used?

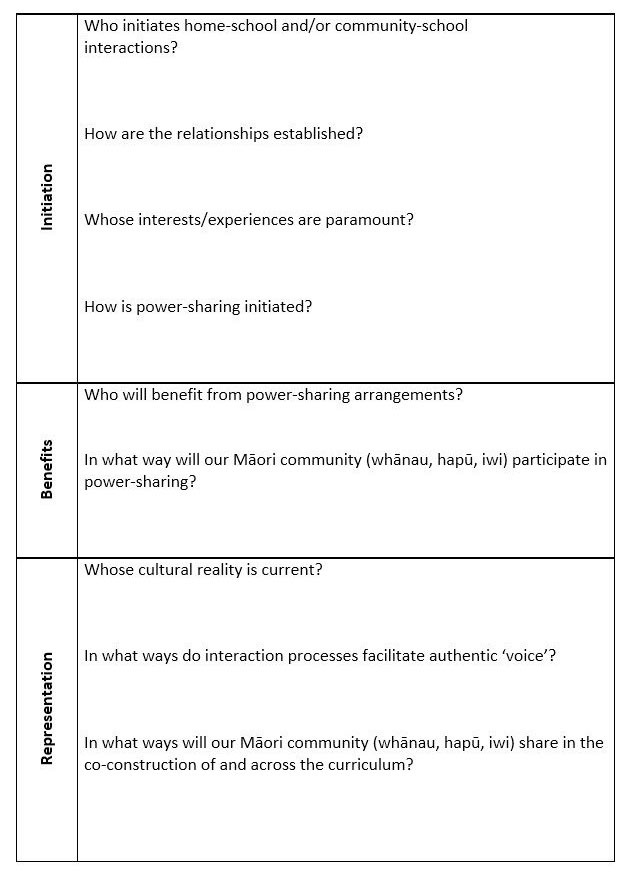

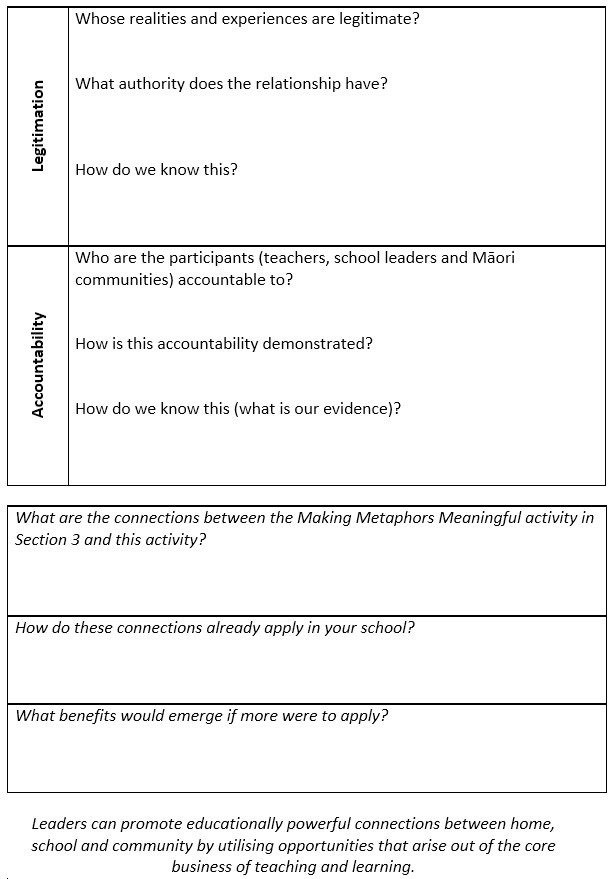

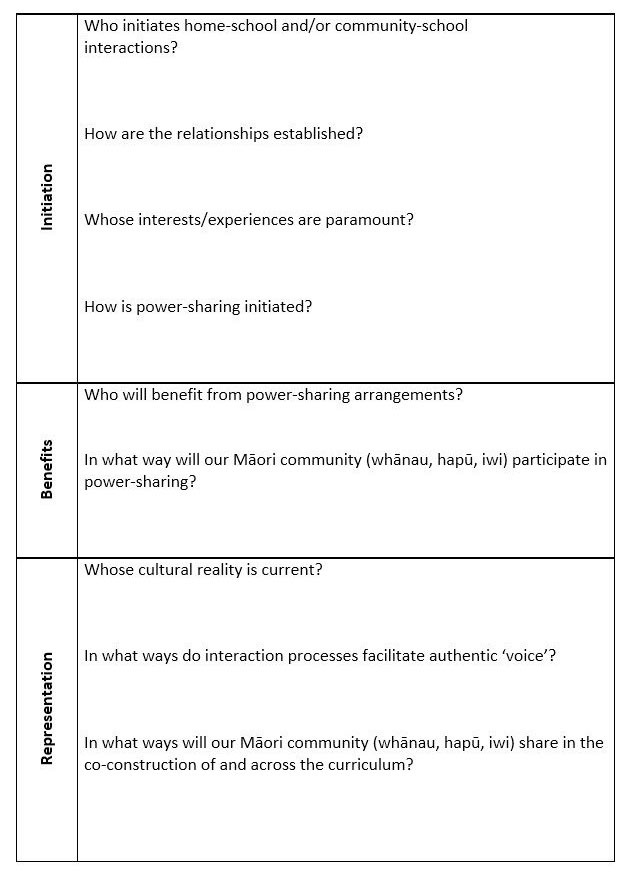

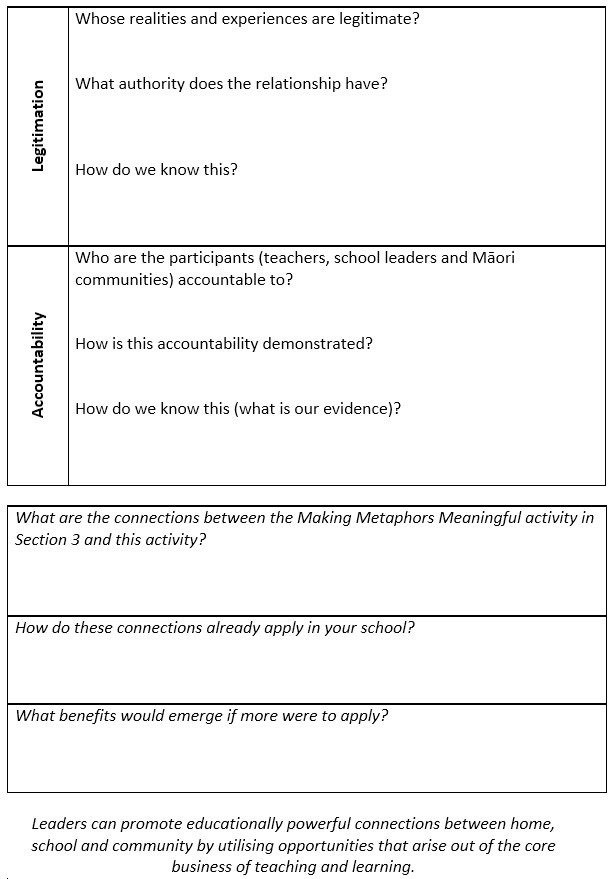

In examining power relations in education, Bishop and Glynn (1999) propose a framework that encompasses five issues associated with power, namely: initiation, benefits, representation, legitimation and accountability (IBRLA). They utilise the IBRLA framework to suggest a model for planning and evaluating educational activities in schools and classrooms in relation to the Treaty of Waitangi principle of partnership (p.199). This framework can be adapted and applied to be used by schools as a means of discussing, planning and evaluating how they engage in the process of developing educationally powerful connections with Māori whānau and communities.

Use the framework provided in Resource 3 below to discuss and consider how the IBRLA model applies in relation to home-school partnerships with Māori whānau and community. Detail current practices and possible alternative practices that you might explore.

16

17

Culturally responsive pedagogy

of relations

Evidence from Phase 5 schools in Te Kotahitanga has demonstrated that when a culturally responsive pedagogy of relations is embedded in classrooms, and across the school, Māori students are more likely to experience education success (Alton-Lee, 2014).

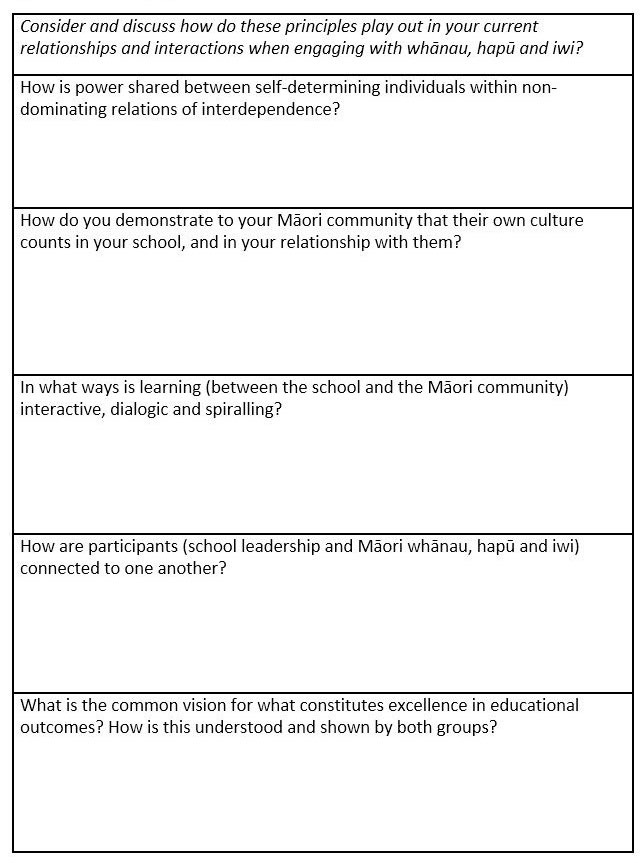

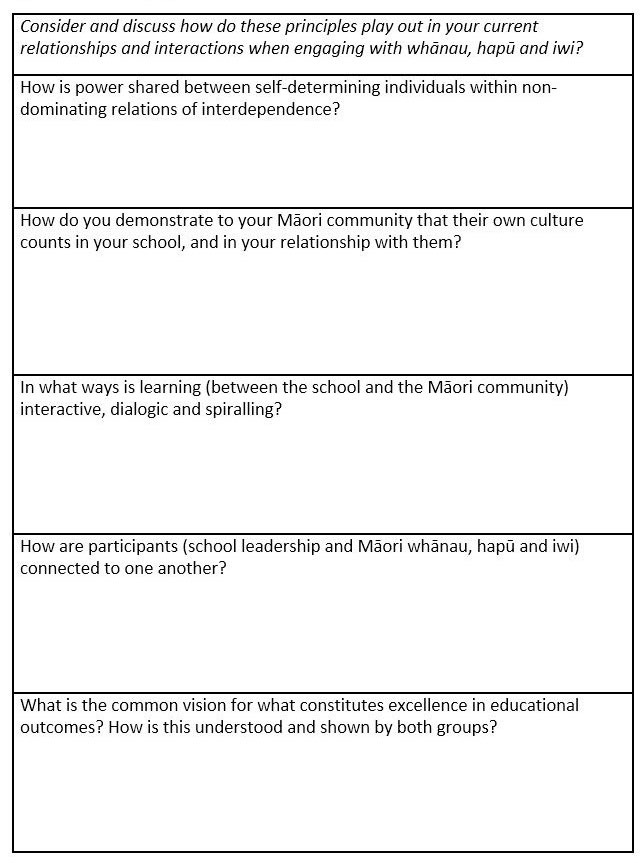

When considering home and school relationships and interactions with Māori whānau, hapū and iwi members it is useful for school leaders and teachers to evaluate themselves in relation to a culturally responsive pedagogy of relations. This requires being able to contemplate the extent to which their own school reflects a context:

- where power is shared between self-determining individuals within non-dominating relations of interdependence

- where culture counts

- where learning is interactive, dialogic and spirals

- where participants are connected to one another; and

- where there is a common vision for what constitutes excellence in educational outcomes (Bishop et al., 2007).

Culturally Responsive Pedagogy

of Relations

[Download 4]

18

Collaboration – theory

and practice

The concept of collaboration in educational settings is

not clearly defined within the literature. One academic

(Hynds, 2007) even goes so far as to suggest that the literature has resulted in “competing definitions” (p.11)

and a “confusing array of terms” (p.12).

In her Masters thesis, Sweeney (2011) investigated collaboration within and between schools, suggesting

that it was possible to gain clarity about the concept by focusing on the purposes of collaborative practices.

Based on her review of the literature, she proposes two broad and interconnected purposes for effective collaboration in education, namely: “for teachers and students to learn and improve” and “for those working together to reach a common goal” (p.18).

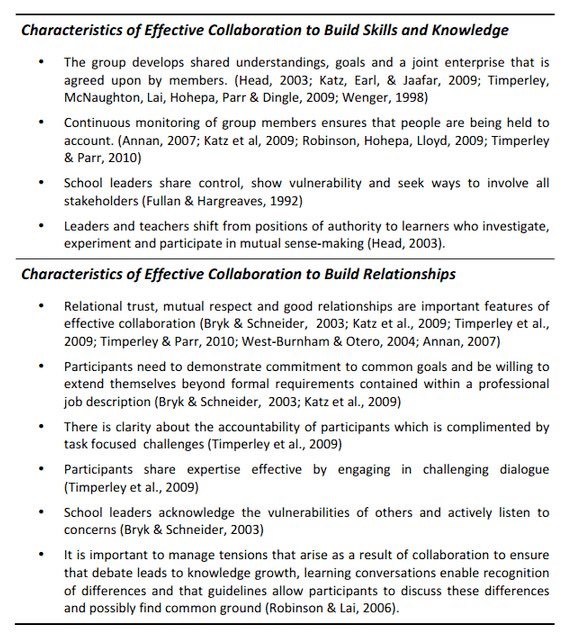

She further suggested that collaborative groups that have been successful in raising student achievement are characterised by particular practices that, again, fall into two broad categories: “building skills and knowledge”

and “building relationships” (p.27).

While Sweeney’s research is specifically focused on collaboration between educational practitioners (i.e. teachers, school leaders and professional development providers), the collaborative practices identified within the literature can be expanded to encompass family and community members and applied as indicators of effective collaboration between home and school stakeholders.

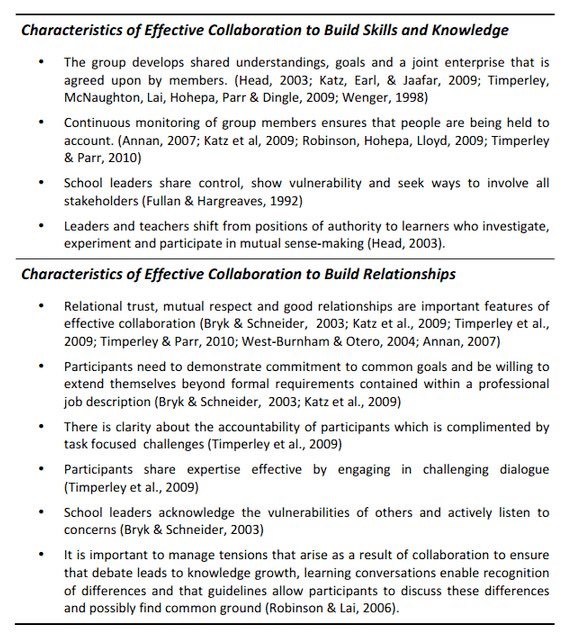

In summarising the literature, Sweeney has developed

a table of specific indicators of effective and ineffective collaborative practices associated with building skills and knowledge and building relationships. The table below details indicators of effective collaborative practices that are relevant to home-school collaboration and is an adaptation of Sweeney’s summary (p.41-43).

19

Sweeney’s summary

Collaboration in practice: conversations with

Mere Berryman and Ted Glynn

In two separate interviews about home-school collaboration, Mere Berryman (2010) and Ted Glynn (2011) responded to questions about how schools should make connections to and engage with Māori communities.

From these interviews, four common themes emerged. These themes are:

- identify who you are

- build relational trust

- listen to communities; and

- respond accordingly.

An explanation of each theme, and some strategies that schools could implement to address these four themes,

are detailed as follows.

20

1. Identify who you are

Whether you are a school leader, a researcher or a teacher, Māori communities want to know who you are – not necessarily what you are, but who you are.

Rituals of engagement such as pōwhiri and hui provide powerful opportunities for Māori to see who you are. Knowing who you are in part helps the community to determine their own connections with you and to also assist them to begin to ascertain where you are coming from.