4

Creating responsive social contexts for writing

Sociocultural understandings of human development and learning promote a view of learners as active agents who come to know their world in terms of their own operations within it, especially through their use of language in contextualised social interactions with others (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Bruner, 1996; Glynn, Wearmouth, & Berryman, 2005; McNaughton, 2002; Vygotsky, 1978).

Lave and Wenger (1991) construe learning as a process of change in the degree to which individuals can actively participate in and be included in communities of practice where there is regular and sustained interaction with more-skilled individuals around genuinely shared activities (Wearmouth & Berryman, 2009). Genuinely shared activities are those that are meaningful and authentic for students.

Regular interactions around these shared activities can lead students to develop and refine their knowledge and skills within specific literacy domains such as speaking, reading and writing for example. Sustained participation in these activities also affirms and extends positive social relationships. Glynn, Wearmouth and Berryman (2005) describe these important interactive and social learning contexts as responsive social contexts. Glynn et al. (2005) further explain that:

Responsive contexts are characterised by a balance of control over initiating and continuing learning interactions, such that the more-skilled participant takes on a range of responsive, interactive roles rather than instructional, custodial or managerial roles.

They are characterised also by reciprocal intellectual and social benefits for each participant that result from their language interaction around shared tasks. These contexts may be characterised, too, by frequent reversal of the traditional learning and teacher roles, and by feedback that is responsive rather than evaluative (p.93).

5

In establishing responsive social contexts for writing, teachers avoid traditional pedagogical approaches that emphasise evaluation of the text and in particular focus on formal instruction in surface features (such as grammar, spelling and punctuation).

By contrast, responsive teachers understand that students need to be able to share their prior knowledge and experiences through the medium of writing, without fear of criticism or failure, therefore they work to create contexts in which students have many opportunities to communicate with others through writing.

This involves ensuring that students receive feedback about their writing from people who are more skilled at writing and it also involves providing strategies and writing structures that support students to generate words and organise their ideas in the planning and revision processes of writing.

Research reported in Alton-Lee’s (2003) Quality Teaching for Diverse Students in Schooling: Best Evidence Synthesis supports the proposition that effective pedagogical approaches to writing build upon the language experiences of diverse students and view writing as both a social as well as a literacy skill. Alton-Lee draws specifically from the work of Freedman and Daiute (2001) who highlight the importance of acknowledging that many students enter schools and classrooms with language practices that are different from those valued in formal writing genres of mainstream schools.

Alton-Lee surmises their findings and proposes that “addressing diversity is the key pedagogical strategy for effective instructional approaches in writing” (p.24).

This research further highlights the importance of teacher consideration of their pedagogical approaches to writing and the way in which the socio cultural contexts they create are inclusive and enable all learners to actively participate in the classroom writing community.

6

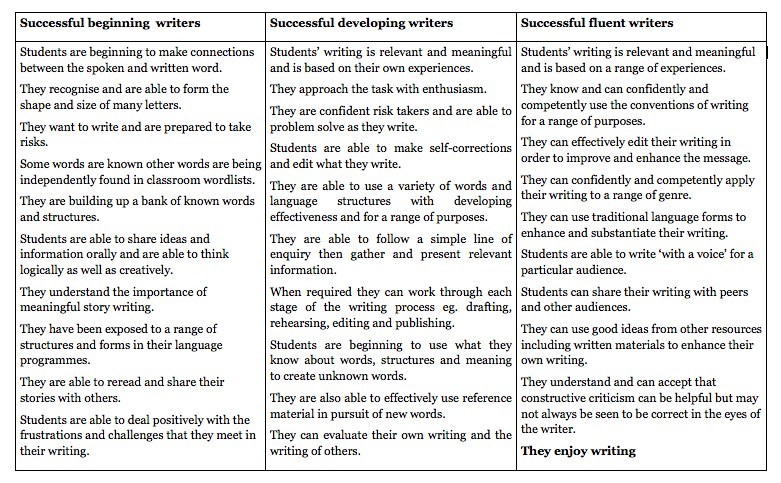

The development continuum reflects some indicators of successful writers — what does writing for success look like?

7

Responsive Written Feedback

Theoretical Basis — the Responsive Written Feedback procedure

Responsive Written Feedback is an example of a writing procedure that draws from sociocultural understandings of learning to accelerate the writing achievement of students.

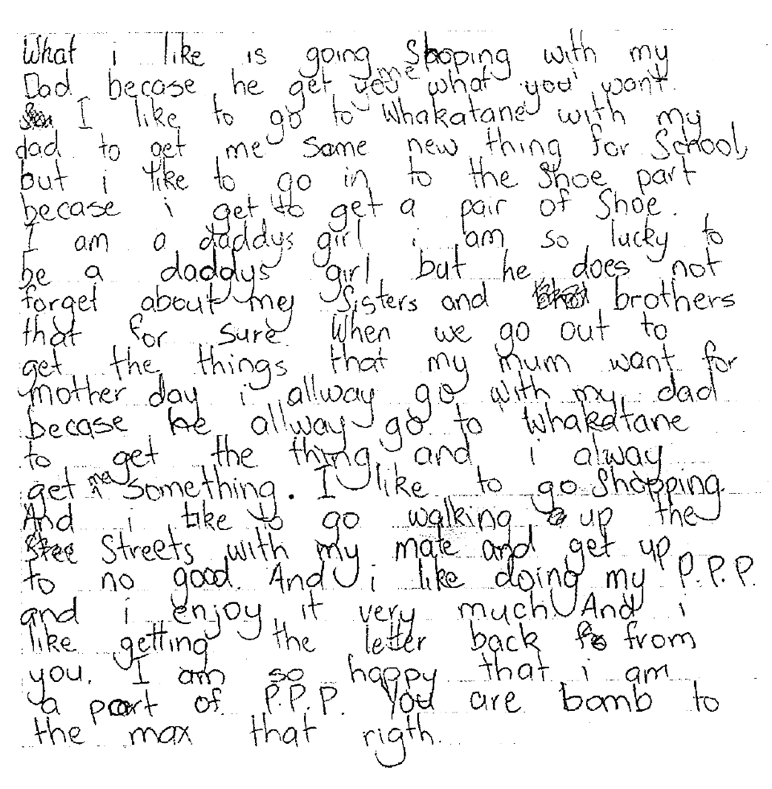

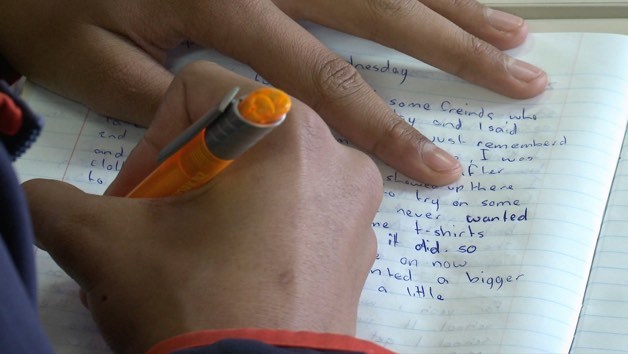

The procedure provides a framework that facilities social interaction, through a writing exchange or writing relationship, between a (less competent) writer and a responder (who is more skilled at writing than the writer).

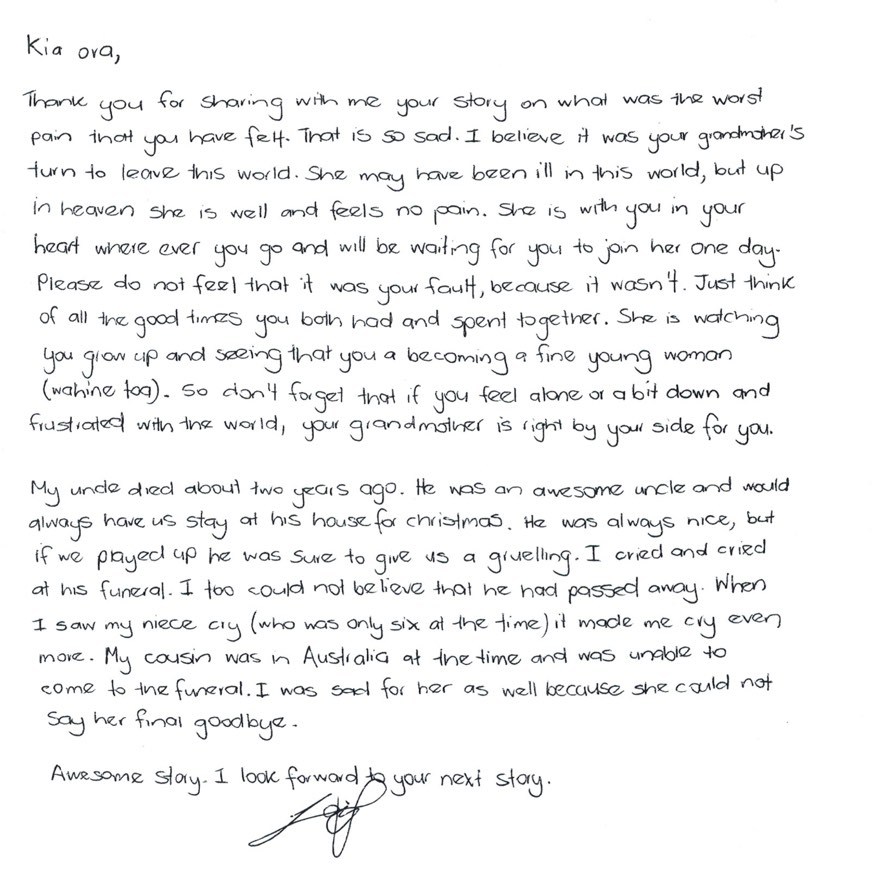

The writer initiates the writing exchange and can determine what they would like to communicate and share with their responder. The responder reads the piece of writing and then provides written feedback to the writer.

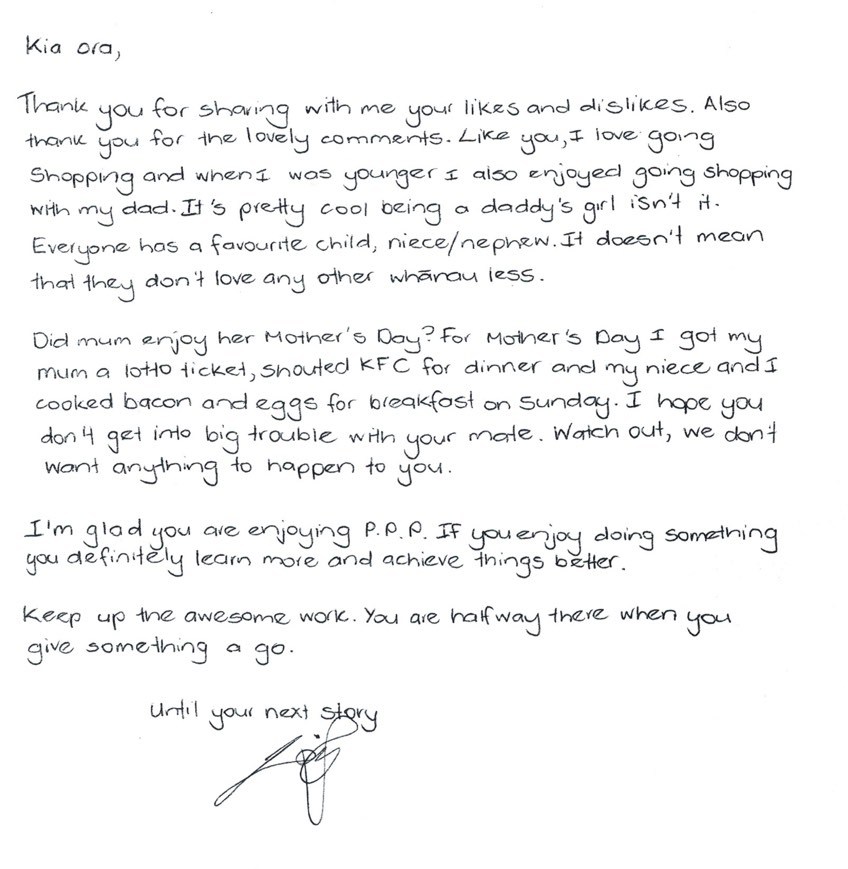

The intention of the feedback is to respond to the messages conveyed within the piece of writing in order to develop a non-dominating writing relationship between the writer and the responder.

If we consider what this social interaction might look like in terms of a respectful face-to-face conversation between two people, the person who is more competent in their oral language delivery is unlikely to focus on correcting or evaluating the oral language delivery of the person who is less competent.

The same principle or socially appropriate conventions apply to this writing exchange so that the responder shows support for the writer by responding to what they understand the writer is attempting to communicate, rather than commenting on or trying to correct the writer’s errors. This does not mean however that Responsive Written Feedback does not support the development of accurate spelling, grammar and correct structure.

If we again consider the face-to-face conversation scenario, the person who is more competent in their oral language delivery has the opportunity to provide a correct example or model of oral language conventions and structures when they verbally respond to the person who is less competent.

8

In this sense the person responding is ‘showing’ what speaking correctly sounds like rather than specifically ‘telling’ the less competent person where they need to be corrected.

Similarly in the writing context the responder has the opportunity through their written response to show the writer what correct spelling, grammar, punctuation and/or structure looks like, while at the same time they show the writer (again through their response) that they understand and value the message the writing is conveying.

Responsive Written Feedback was used in research undertaken by Glynn, Jerram and Tuck in an English language context in 1986 and 1988.

This procedure was then further trialled in a Māori language setting (Glynn, Berryman, O’Brien and Bishop, 2000), in the context of immersion students transitioning into the English language and in the context of emergent writers in both English and Māori (Glynn, Berryman & Glynn, 2000).

More recently the Responsive Written Feedback has been used in Te Kotahitanga in a mainstream secondary school to accelerate the writing achievement of Year 9 students.

In these studies both adults and tuākana (older students) have been used as responders. The results showed that all students (including tuākana), who participated, learned the procedures easily, wrote longer and more interesting pieces of writing and improved their writing fluency across a range of different measures.

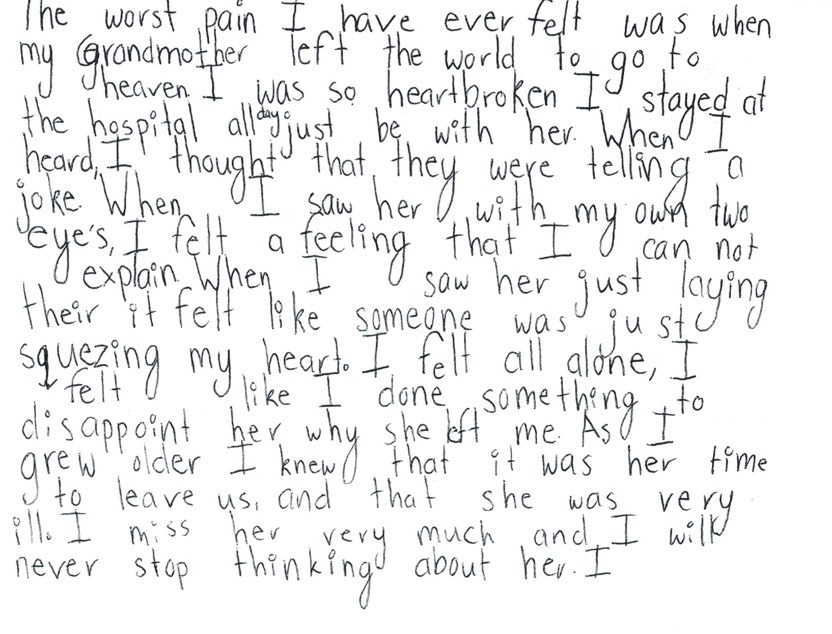

An additional pastoral benefit that one teacher observed in the Te Kotahitanga study reinforces how powerful this procedure can be with regard to providing a context for learning whereby students through their engagement in this sustained social interaction could come to better understand and participate in their world.

She specifically referred to a Year 9 male student who did not initiate interactions and rarely engaged with herself and other students in class.

However, the teacher noted that as this student’s writing relationship developed with his responder (who was a senior male student) his writing progressively became more expressive and detailed as he shared his thoughts and feelings and sought out his responder’s experiences and advice.

In one exchange the teacher noted that the writer had written to his responder about his father leaving the family home and he shared that he found this very difficult. He explained that he deeply missed his father and he found the extra responsibilities that he had as a result of his father’s absence sometimes overwhelming.

9

When the teacher spoke with the responder about how he might respond to this message, the older boy assured her that he knew exactly what he could write back because he had experience of what the writer was going through and he felt confident that he could offer him some advice and support.

The teacher reflected on this, and the written exchanges that ensued between this pair, and conceded that the writer had not felt that he could share this private and sensitive information about himself with her, but he had felt safe and secure to do so with his responder, through his writing.

This writing intervention had provided her with an opportunity to get a different insight into her student and develop a deeper understanding of who he was and what he was going through.

Importantly, the intervention also provided a safe forum for the writer to share his thoughts and feelings with another person, be heard (through his writing), receive some support and advice, and subsequently come to better understand his world and his agency within that world.