21

Sustaining and scaling school-wide reform

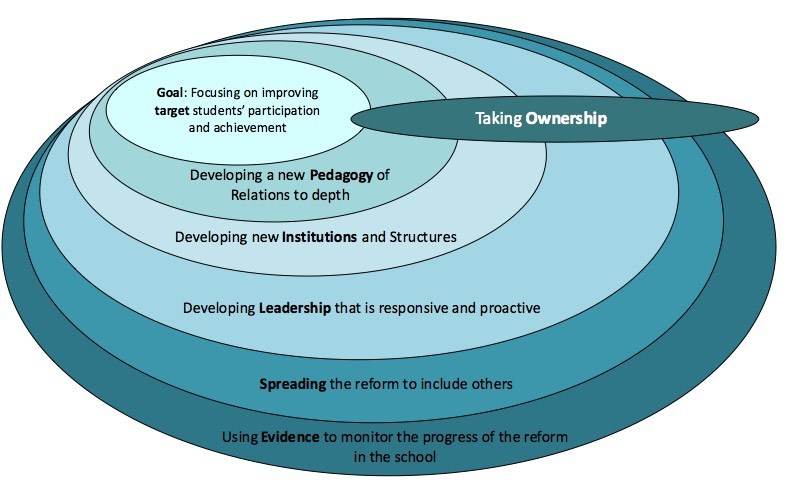

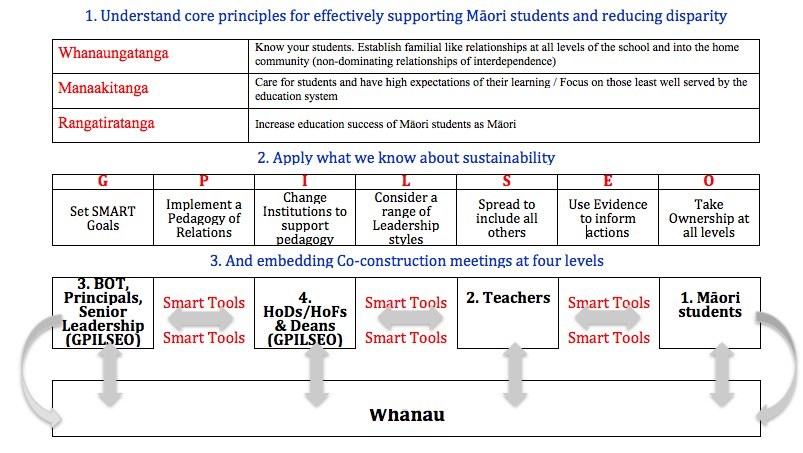

A significant starting point in the search for a model for a sustainable and scaleable school-wide reform was the large meta-analysis conducted by Cynthia Coburn (2003).

Most of the studies Coburn reviewed were of schools in their first few years of implementing a new, externally generated reform.

In considering how to take a project to scale in a large number of classrooms in a school, how to sustain the gains made in these classrooms and schools, and how to take the project to other schools once it has proven to be successful in the initial schools, Coburn identified four main components, these being:

- pedagogy

- sustainability (essentially meaning institutionalisation)

- spread

- ownership.

However, in light of our experiences in Te Kotahitanga and the literature reviewed for Scaling up Education Reform: Addressing the Politics of Disparity (Bishop, O’Sullivan & Berryman, 2010), we further developed the Coburn model by adding three more components, these being:

- the need for an unrelenting focus on improving Māori (or any target) students’ educational achievement

- the need for leadership that is proactive, responsive and distributed

- the need to develop further evaluation and monitoring instruments, along with the need to raise the capacity and capability of staff in the schools to undertake this evaluation and monitoring.

From this list the following model (Figure 6) was developed within a study that ran parallel to Te Kotahitanga and that was funded by Ngā Pae o te Māramatanga.

Initially, the model was first published as a monograph (Bishop & O’Sullivan, 2005) to both identify the necessary change dimensions and provide a tool for monitoring the progress of the reform.

22

GPILSEO [Download 5]

Figure 6: GPILSEO model

It is important to go back to these seminal documents to get a full understanding of the GPILSEO model and how we have used this model in Te Kotahitanga to contribute to scaling up the education reform.

Bishop, R., & O’Sullivan, D. (2005). Taking a reform project to scale: Considering the conditions that promote sustainability and spread of reform. A monograph prepared with the support of Ngā Pae o te Māramatanga, The National Institute for Research Excellence in Māori Development and Advancement. Unpublished manuscript.

Bishop, R., O’Sullivan, D., & Berryman, M. (2010). Scaling up education reform: Addressing the politics of disparity. Wellington, New Zealand: NZCER Press. In this section, we use the GPILSEO model to focus on the actions that those at the school level need to take to develop, implement, sustain, and extend a theory-based reform. This begins at the classroom level.

GPILSEO at the classroom level

The GPILSEO model can help us to understand what a reform initiative requires if it is to bring about sustainable change within classrooms, and also, what is required if it is to be spread to other classrooms. In terms of GPILSEO, this requires:

- Goals: A clear focus on improving the engagement, participation and achievement of the students being targeted by understanding, developing and implementing a pedagogy proven to be effective.

- Pedagogy: A means of implementing this proven pedagogy consistently and with integrity, so that teachers and in turn all students can understand and implement the new practices. This requires teachers understanding the new theories of practice, in their day-to-day classroom relationships and interactions with students and teaching colleagues.

23

- Institutions: A consideration that pedagogical reform might require new institutions (changes to systems or structures) in classrooms. For example desks in rows might not be the best system for undertaking a more relational, dialogical approach to pedagogy.

- Leadership: A relational, dialogical approach to pedagogy may see different and more distributed opportunites for leadership to emerge. For example it will promote people as being initiators of their own learning and who take responsibility and leadership for supporting the learning of others.

- Spread: New classroom relationships and interactions will need a means whereby they are able to be spread to include all students (across classrooms and across year levels) and all teachers (across departments/faculties) in the school.

- Evidence: A means whereby the progress of all students can be monitored to inform the ongoing changes in instructional. The gathering and examination of classroom evidence provides practice.

- Ownership: New understandings and practices must be owned and understood by all members of the school and they must begin to move out into the community.

24

Activities

The following video clips offer a view into how GPILSEO may look at the classroom level and in different contexts