Mahi T

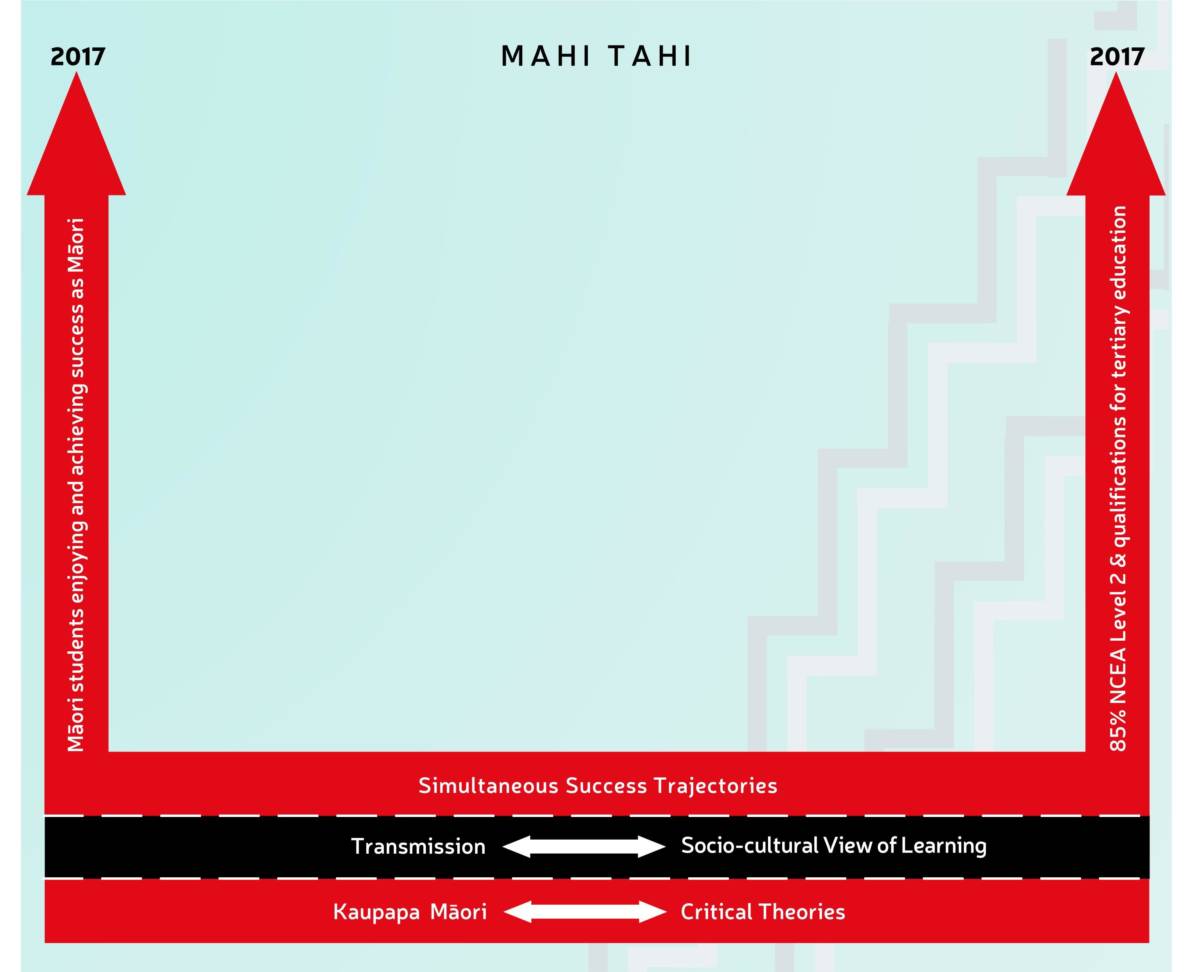

1. Kaupapa Māori and critical theories

Kaupapa Māori and critical theories are the Kia Eke Panuku foundations that guide the actions of Strategic Change Leadership Teams in their work with schools, whānau and Māori communities.

2. Disrupting the pedagogical status quo

Traditional transmission teaching continues to be the dominant pedagogy in many secondary schools. In Culture Speaks (Bishop & Berryman, 2006 (1), Māori students said they understood why they needed this but they also wanted to have a say in their learning and share their ideas with others. This type of pedagogy comes from a socio-cultural view of learning (Vygotsky, 1978 (2). Thinking about how learning happens and linking across this range of teaching pedagogy to make professional curriculum decisions is essential.

In Kia Eke Panuku, the importance of a socio-cultural view of learning is understood across a range of contexts. While this begins with classroom pedagogy where we are learning from each other (ako), at the side of the more knowledgeable other, whomever or where ever that knowledge might come from, it does not stop here.

Rather than an over-reliance on transmission or transactional practices, a socio-cultural view of learning can also guide how we make decisions across the school. This can inform how we learn from our colleagues across departments and curriculum areas. It can also inform how we broker relationships to engage with whānau and the Māori community.

In the diagram, the broken lines between these elements represent the permeability of these boundaries, while the arrows pointing in both directions at the same time, reflect these ways of thinking and behaving are not distinct but are constantly and inter-dependently in play.

This theoretical framework, moving beyond equality to more equitable practices, is clearly visible at every level of Kia Eke Panuku reducing disparities of outcomes by supporting Māori students to be successful as Māori in the daily life of schools.

(1) Bishop, R., & Berryman, M. (2006). Culture speaks: Cultural relationships and classroom learning. Wellington: Huia Press

(2) Vygotsky, L. (1978). Mind in society. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

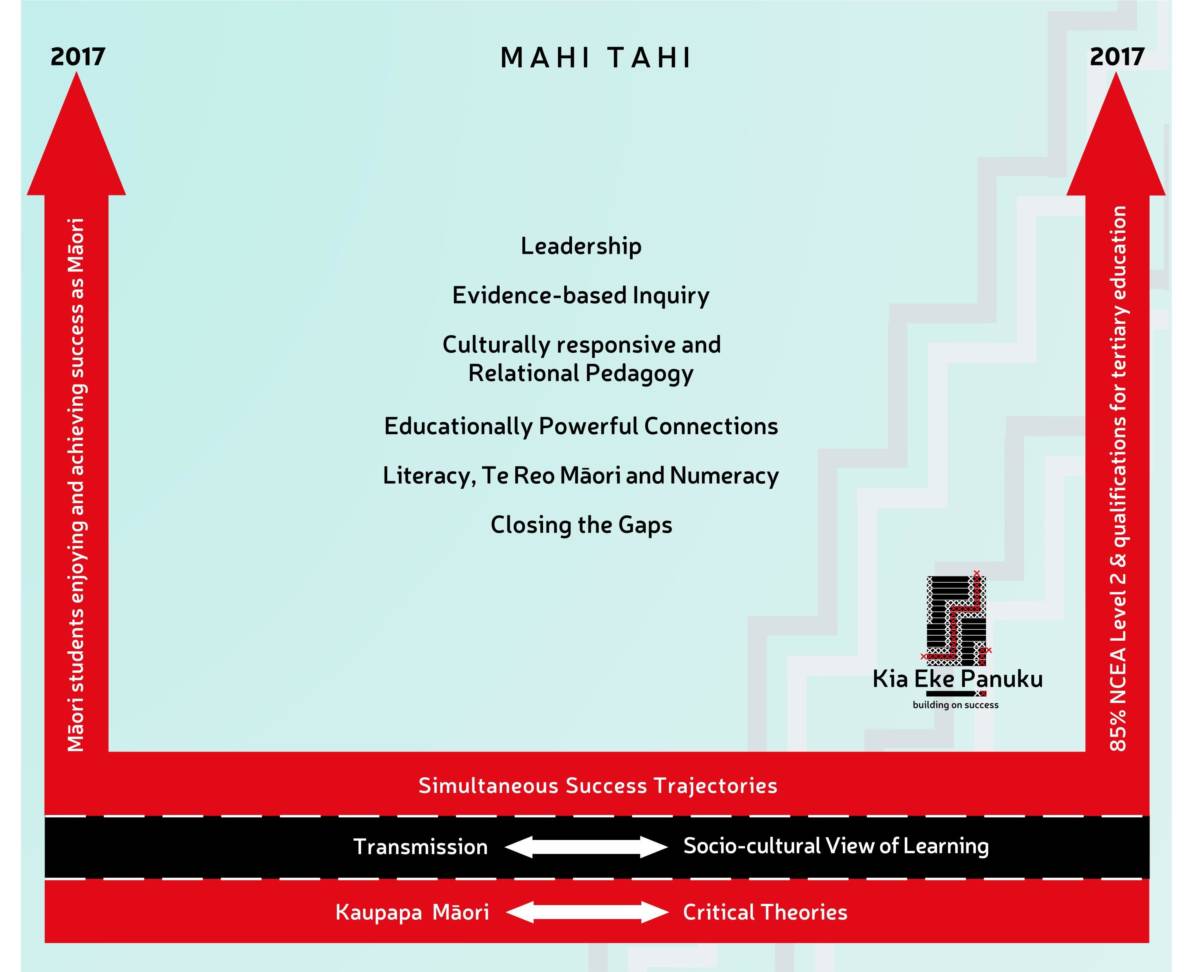

3. Mahi Tahi

Mahi Tahi provides the unrelenting focus, principles and tools for working in schools towards the simultaneous success trajectories of:

- Māori students enjoying and achieving education success as Māori and

- 85% of Māori students achieving NCEA Level 2 and qualifications for tertiary education.

This dual focus activates the widespread system reform required to achieve the explicit kaupapa of Kia Eke Panuku: Secondary schools giving life to Ka Hikitia and addressing the aspirations of Māori communities by supporting Māori students to pursue their potential.

Voices: Treaty of Waitangi (PDF)

-

Ka Hikitia

Ka Hikitia - Accelerating Success 2013-2017 is the Ministry's strategy to rapidly change how the education system performs so that all Māori students gain the skills, qualifications and knowledge they need to enjoy and achieve education success as Māori.

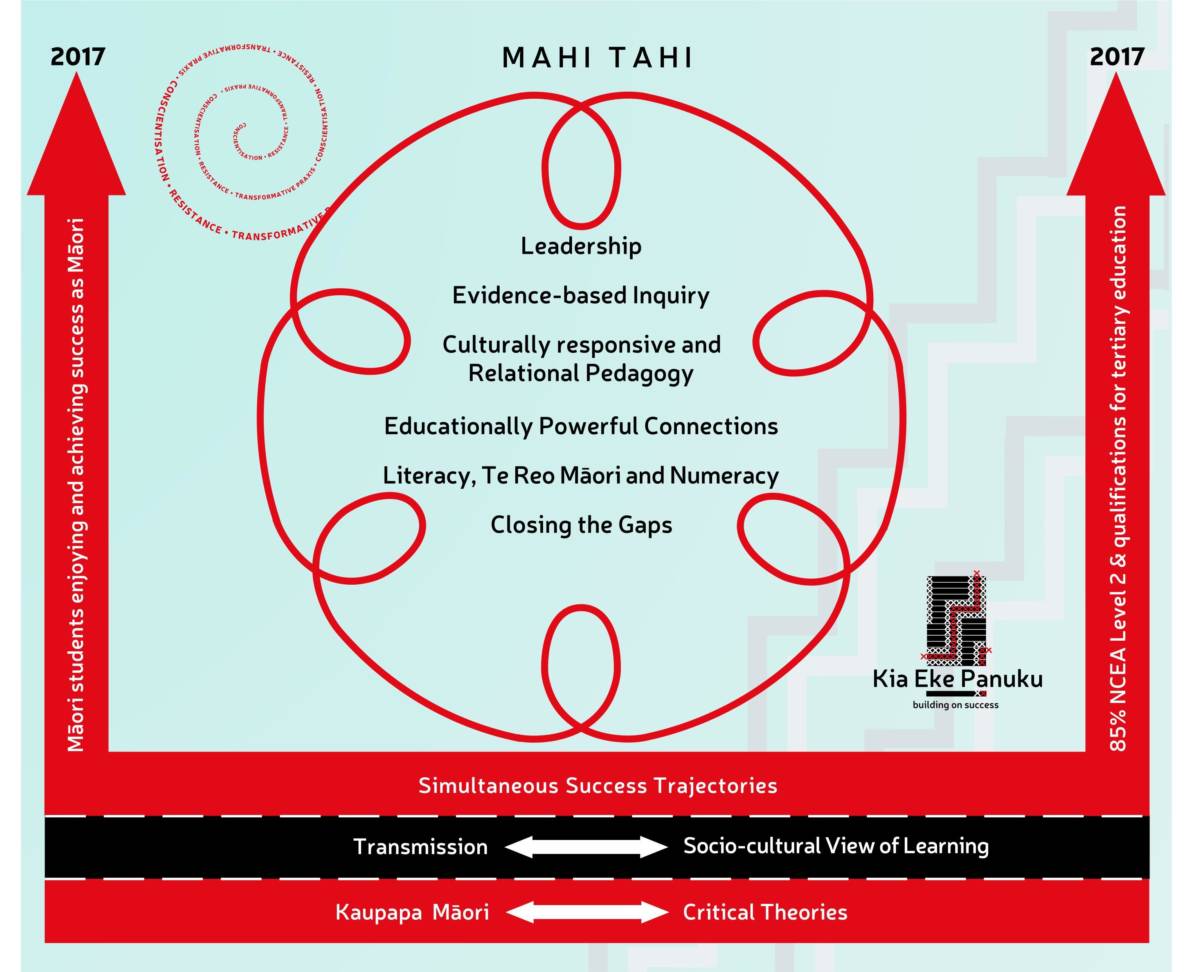

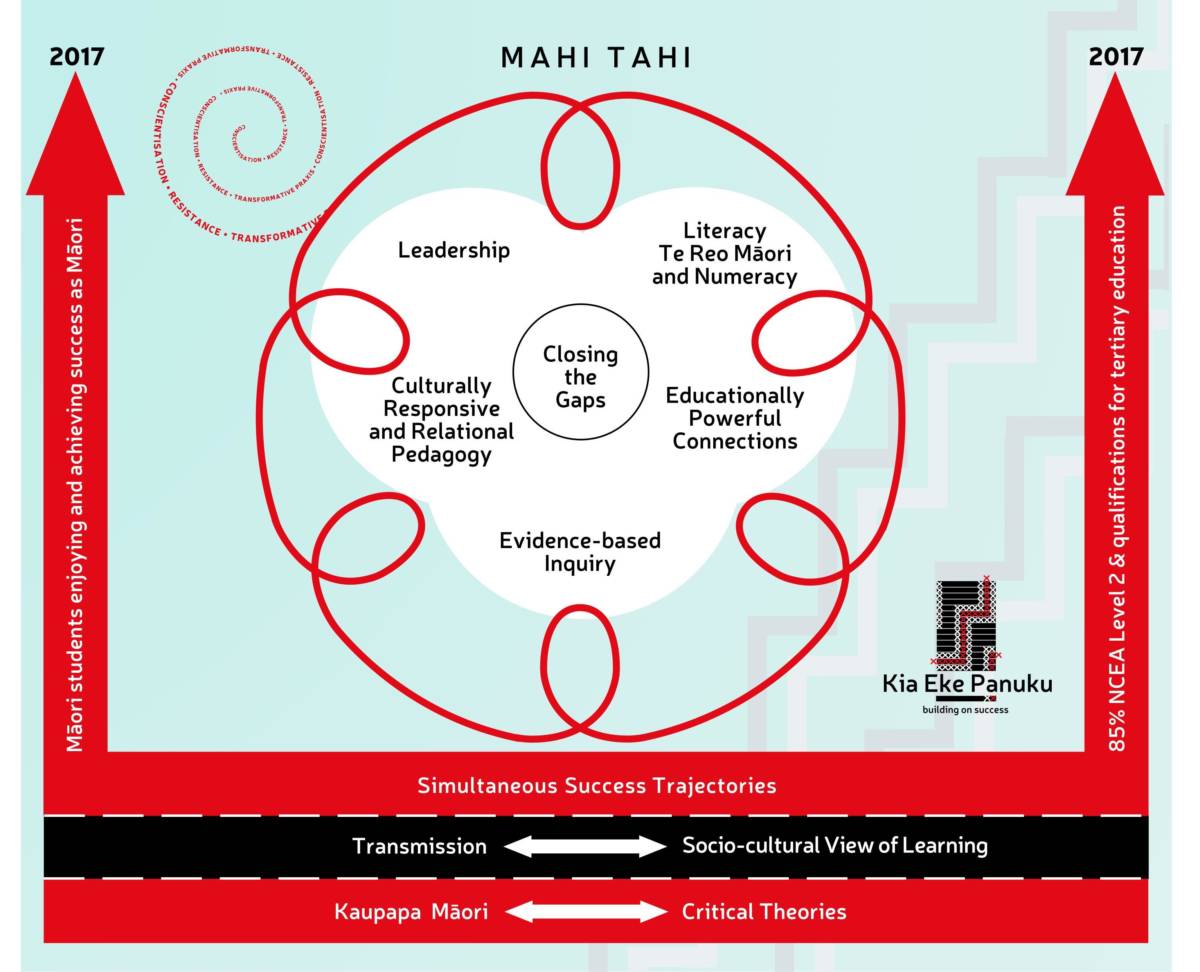

4. The dimensions

Kia Eke Panuku uses the following five dimensions as levers for accelerated school reform toward closing the gaps between Māori students and their non-Māori peers.

These dimensions are:

- Leadership

- Evidence-based inquiry

- Culturally responsive and relational pedagogy

- Educationally powerful connections with Māori

- Literacy, te reo Māori and numeracy

Closing the gaps requires the spread and ownership of all of these dimensions coherently across the school and across the system.

The personal commitment of all, to the dynamic interplay of these dimensions, can effect transformative change for Māori students and their communities.

- go to: Dimensions of Change section

5. Spiraling critical cycle of self-reflection

In Kia Eke Panuku school leaders and teachers work constantly within a dynamic and spiraling critical cycle of self-reflection, learning, unlearning and relearning.

Evidence of outcomes for Māori students alongside evidence of current practice informs new understandings of the implications of current practice (conscientisation).

School leaders and teachers then decide what they are doing that needs to change (resistance).

Then they can begin to implement those changes in order to lead to accelerating improved outcomes for Māori students (transformative praxis).

- view: Ako Critical Cycle (PDF)

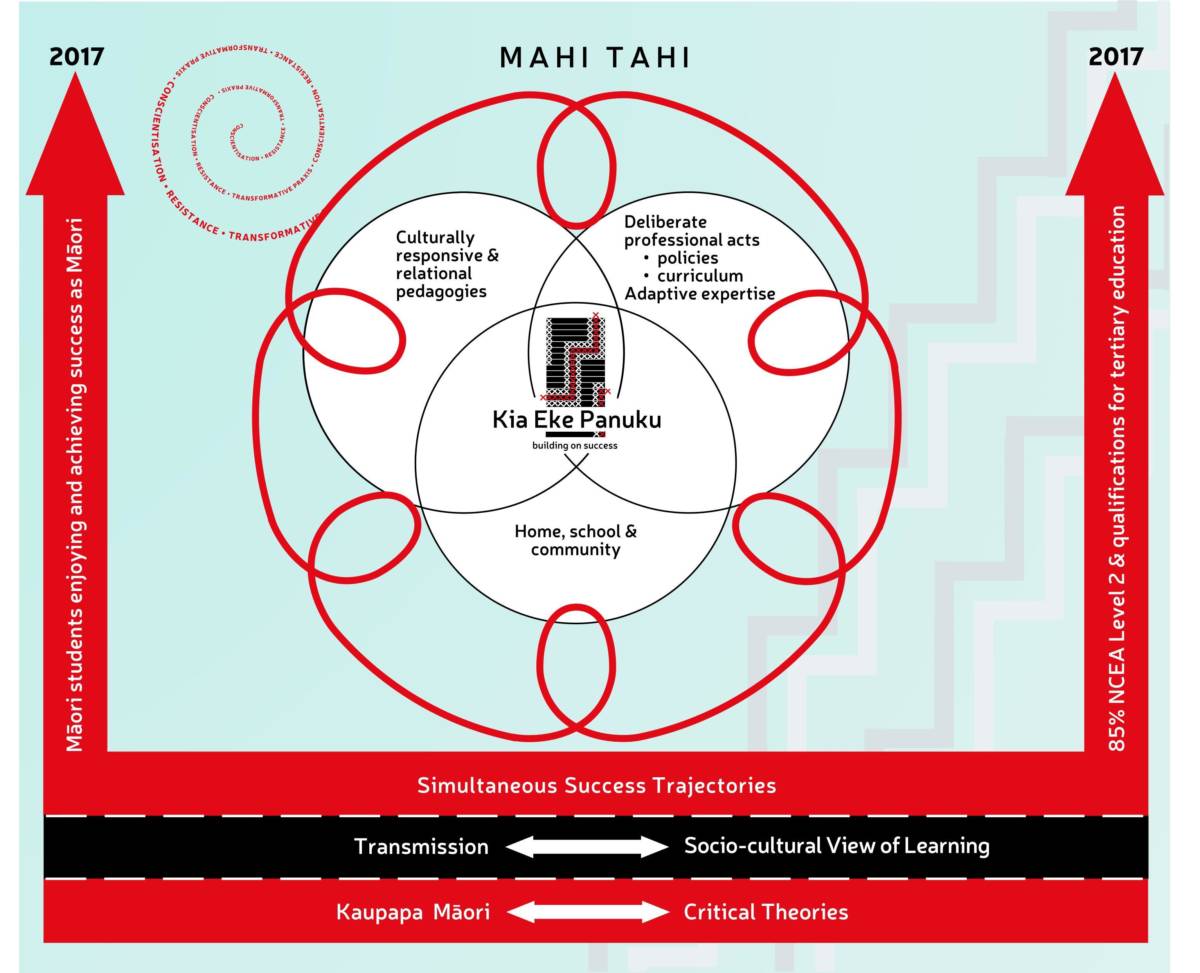

6. The ako: critical contexts for learning

Within the simultaneous success trajectories of Ka Hikitia, the ako: critical contexts for learning concept has been developed to support learning around three specific contexts:

- deliberate professional acts,

- culturally responsive and relational pedagogies and

- home, school and community collaborations.

These contexts for learning can be used to achieve the deep, systemic and sustainable change across the five dimensions of Kia Eke Panuku.

The contention is that for systemic and ongoing reform in any or all of these dimensions, Strategic Change Leadership Teams should concern themselves with enacting all three contexts for learning/levers, simultaneously and with complementary, inter-dependent actions.

In so doing the reform can be enhanced and accelerated to align the practices of the Kia Eke Panuku kaupapa more quickly and succinctly across the systems and institutions within schools, but also from school to school.

It is expected that this model is responsive to each school’s evidence (both qualitative and quantitative) of Māori students’ participation and achievement and their community’s aspirations for the future potential of their tamariki mokopuna. Individual contexts may be being partially or more fully engaged with depending upon where the school is positioned.

Boundaries surrounding these contexts are permeable and open to knowledge creation through the sharing of new knowledge, resources and practices.

To inform our own critical understandings of pedagogy and help us to understand what needs to change if we are to move towards accelerated improvements for Māori students, threaded together, throughout the critical contexts for learning is the Ako: critical cycle of learning.

Those engaging with systemic and ongoing reform should therefore concern themselves with enacting all three critical contexts for learning/levers, simultaneously and with complementary, inter-dependent actions. In so doing the reform can be enhanced and accelerated to align the practices of the Kia Eke Panuku kaupapa more quickly and succintly across the systems and institutions of the school.

7. Conclusion

Mahi Tahi requires teachers and leaders to work alongside whānau, hapū and iwi, to recognise the socio-cultural context in which they work and their agency to transform it.

This is essential in order to improve Māori student outcomes and realise the aspirations of the Treaty of Waitangi.

The sole proviso is that true, wide-scale and transformative reform takes time. The process of transformative change is complex, difficult and different for every community.

As Fullan says (1), this is “Never a checklist, always complexity.

There is no step-by-step shortcut to transformation; it involves the hard, day-to-day work of re-culturing.”

Securing access to simultaneous trajectories for Māori learners is fundamental to Kia Eke Panuku schools. One school shares some the shifts they have made to transform the learning environment in the Ka Hikitia video kete.

(1) Fullan, M. (2002) Beyond Instructional Leadership in Educational Leadership Vol 59 (8) pp.16-21.